Quote

"Your writings on the topic of Liszt and key-characteristics, which have occupied so much of your professional life, are important and make a difference. Not all musicologists are able to make such a claim."

(Alan Walker)

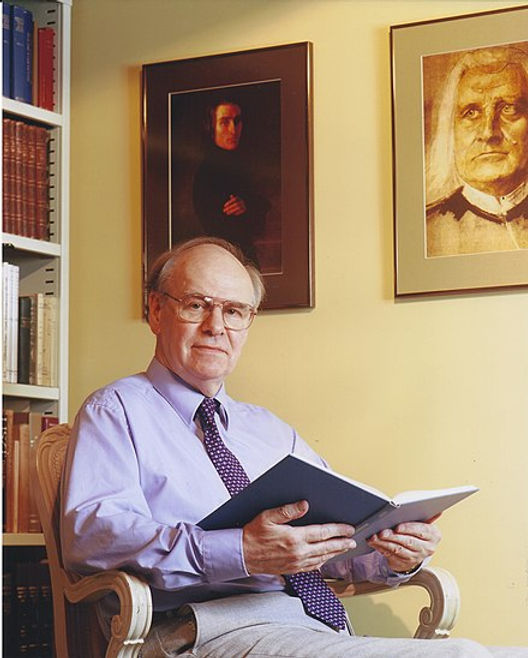

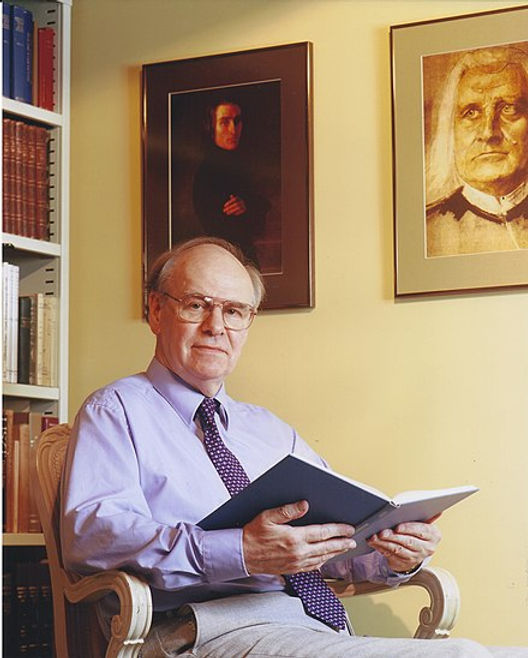

This website is intended to direct visitors to my writings on Liszt’s treatment of key as programme. The name of this topic – in the days when it was talked about in academic circles – is key characteristics. Today the subject is ignored – probably because the attempt to give it any semblance of scientific objectivity has been abandoned. But here the question is not one of a general musical theory, but rather one of a particular composer’s personal relationship to it in his music. The suspicion that Liszt’s approach to musical composition was haphazard, improvisatory, and ultimately chaotic has led to many conclusions about him not only as a musician, but as a man. This includes schizophrenia. But Liszt functioned at the point where music touches reality – by which he meant not only mountains and rivers and paintings and literature, but human emotion, religion, and death. All these things are constant. As are the keys he was forced to use in their depiction. There is only one C major, there is only one D minor. Their character is real and to that extent delineated. Furthermore it is the reality of this character that can lead to its omission – at least in the imagination. Key characteristics mean they can be obliterated.

I began to research the matter when I noticed the tendency of Liszt to use certain keys in similar situations – in particular E major, A flat major and D minor. At this point I discovered that the catalogues of his music omit the keys. I had no choice therefore but to look for this information myself. After examining 392 works, I considered I had enough information for it to be regarded as statistically significant. Over the years a number of articles by me on the topic have appeared, and my conclusions are summed up in the book Liszt’s Programmatic Use of Key published in 2021.

I give here some of my articles in pdf format – including the book. Otherwise links are given to where an article may be found. Some of the writings I give are biographical rather than musical, as my life’s journey led me from Oxford to Budapest, where I taught at the Liszt Academy for thirty years. This gave me the opportunity to hear Liszt’s music in situ – especially the church music, which is performed liturgically only in Hungary. During his lifetime Liszt the composer was overshadowed by Liszt the pianist – inevitably we might say. My own desire however was to ditch the piano. Having succeeded, I can say that Liszt does not need it to emerge as a great and self-sufficient composer. His uniqueness was in his head, not his hands.

My final contribution to the topic of Liszt and key is the paper I gave in 2024 in Budapest on the Thirteenth Station from Via Crucis. I was fortunate and honoured that among the audience was Alan Walker, who expressed his enthusiasm for what he heard. Upon his return to Canada I therefore sent him the text to read, and his letter in reply can be read on this website.

My love of Liszt began when I was at school (the film Song without end in 1960 with Dirk Bogarde as Liszt and Jorge Bolet as the pianist on the sound track). It continued at Oxford where we studied the Faust Symphony and became my dominant interest when I found a Hungarian recording of the Gran Mass in Blackwells Music Shop. This was followed by the other settings of the mass, the two oratorios, the psalms, Via Crucis, and the shorter choral works (motets) with organ accompaniment. It led me to explore all of Liszt in so far as that was possible in England – which it was not, as I encountered virulent hostility to the man and his music in the 1970s. Only the pianist was acknowledged – and that grudgingly. His songs, the symphonic poems, the two symphonies, the organ music (apart from the BACH piece) and especially the church music were terra incognita - indeed terra nullius (nobody’s land). The recordings I heard were extremely rare imports from Hungary. So I set off to find the music in its homeland – and discovered a strange situation. Far from being terra nullius the music I was searching for was alive and well behind the Iron Curtain – Liszt’s music of all kinds featured in the concert hall, and the church music – very much off-stage in the Communist State – was sung regularly in the main churches of Budapest. I had found my Eldorado, so I stayed there, and finished writing my doctoral thesis on the religious Liszt, subsequently published in book form by Cambridge University Press as Revolution and Religion in the Music of Liszt. I taught English and Music History in the Liszt Academy, an institution which had remained basically unchanged since Bartók was a young professor there when it opened in 1907. I cannot begin to describe the atmosphere, the ambiance, that characterised the place (since lost after its over-drastic renovation with EU funding in 2010-12). The nearest one can get to it today is to read a book like Leschetizky as I knew him by Ethel Newcombe (available online), an American who was a student in Vienna from 1895 to 1903, and later was Leschetizky’s assistant. Vienna and Budapest were for a hundred years two prongs of a single culture – which in Austria did not survive the First World War, but in Hungary remained basically the same during the Horthy period between the wars and then was cocooned from the West by the Socialist State until 1989. Which was good for me, as I gained an insight into a vanished world – the one that produced the great composers, and which we can no longer experience. It put me into an environment in some respects not dissimilar to the one Liszt knew in the 1880s, even though I was wandering around it in the 1980s. Which was grist to my mill, as I was searching for the point of contact in Liszt where the surroundings of his life gave rise to his music.

I began my writings on the keys with Don Sanche in 1992. The opera had received its first performance in modern times during the 1977 Liszt Festival in London whose organizer, Chris de Souza, had given me a copy of the hand-written vocal score prepared for the use of the repetiteurs. Otherwise the score was unpublished. Using this, I followed the performance, and discovered rather startlingly that the young Liszt used certain keys in the same kind of context as the older Liszt did – namely E major, A flat major, B major, and D minor. Which lent weight to the teenager being the author of the music, and not his teacher Paer. I soon realized that the only way to deal with this topic would be to look at as much music as possible and compile lists of what music is in which key. And then see if the use of say A flat major corresponded over a wider area of his output. This was not a quick process. It involved looking at every page of each work. Liszt changes the key signature more frequently than other composers – for example Chopin and Wagner – so the question of what key was being used often corresponded with the signature that preceded it. I therefore was not engaged in a complicated process of tonal analysis, but rather charting the composer’s use of key signatures. In the end – after years of sitting in the Music Academy Library on Thursday afternoons – I had my suspicions confirmed. A flat major means Love – even to the extent that in Le Forgeron when he set the French text “La vie est rude, Mais l’amour l’adouci” (Life is hard, But love sweetens it), he modulated from E minor for the first line to A flat major for the second line – an illogical procedure called for only by the words.

A conclusion I was forced to come to was that choice of key in Liszt is not an arbitrary matter. It is clear that he regarded the keys as in the end living personalities, as such intimately involved in the content of the music written in them. Because he was an advocate of programme music, which he claimed linked music to words as a kind of literature, many of his works have textual material linked to them, in many cases simply their title, and from this we can deduce the kind of ideas Liszt had in mind when he selected the key. To be artistically consistent, this manner of thinking must continue in works where there is no pictorial or poetic title, to that extent bestowing some kind of programmatic character on them. The chief candidate for this interpretation of his musical thinking is the B minor Sonata, surrounding which is a whole library of controversial writing analysing it from every aspect, including whether it has a programme. I have tried to tackle this question by linking certain thematic identities which I claim exist in the work – especially the so-called “Cross motive” - with the contribution to any programme made by Liszt’s choice of key – or keys. B minor, D major, F sharp major and B major – which form the basic tonal foundation of the work – outline a programme in their own right.

My researches have led me to conclude that when Liszt spoke of musique à programme he was thinking much more deeply about the constituents of his art than have most of his commentators (and critics) that came after him. He doesn’t mean music that tells a story. He means that music as such is a story in its own right. This applies to all composers. There is key character in Bach – as I was enlightened by Professor István Lantos at the Liszt Academy, with examples from the “48”, the St. Matthew Passion, and the B minor Mass. He gave lectures on the topic. The role of choosing a key at a particular time is (was) fundamental to the art of composition. It is a foundation stone of European art music from 1600 to 1900. The time has come to stop pretending it doesn’t matter, and can’t be studied. Musicologists need to devote serious attention to the topic, because as the clock ticks, we are losing contact with the creative springs that produced, in the sphere of culture, some of our greatest and most typical examples of human intelligence.

"Your writings on the topic of Liszt and key-characteristics, which have occupied so much of your professional life, are important and make a difference. Not all musicologists are able to make such a claim."

(Alan Walker)